Simon Wiesenthal It Can Happen Again

| Simon Wiesenthal KBE | |

|---|---|

Wiesenthal in 1982 | |

| Born | (1908-12-31)31 December 1908 Buchach, Kingdom of Galicia, Austria-hungary |

| Died | xx September 2005(2005-09-twenty) (aged 96) Vienna, Austria |

| Resting place | Herzliya, State of israel |

| Nationality | Austrian |

| Occupation | Nazi hunter, writer |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse(s) | Cyla Müller |

| Children | 1 |

| Website | www |

Simon Wiesenthal KBE (31 December 1908 – 20 September 2005) was a Jewish Austrian Holocaust survivor, Nazi hunter, and writer. He studied architecture and was living in Lwów at the outbreak of World State of war II. He survived the Janowska concentration camp (belatedly 1941 to September 1944), the Kraków-Płaszów concentration army camp (September to October 1944), the Gross-Rosen concentration army camp, a death march to Chemnitz, Buchenwald, and the Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp (February to 5 May 1945).

After the war, Wiesenthal defended his life to tracking down and gathering information on avoiding Nazi war criminals so that they could be brought to trial. In 1947, he co-founded the Jewish Historical Documentation Centre in Linz, Republic of austria, where he and others gathered information for hereafter war criminal offence trials and aided refugees in their search for lost relatives. He opened the Documentation Centre of the Association of Jewish Victims of the Nazi Regime in Vienna in 1961 and continued to attempt to locate missing Nazi war criminals. He played a small role in locating Adolf Eichmann, who was captured in Buenos Aires in 1960, and worked closely with the Austrian justice ministry to prepare a dossier on Franz Stangl, who was sentenced to life imprisonment in 1971.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Wiesenthal was involved in two high-profile events involving Austrian politicians. Before long after Bruno Kreisky was inaugurated equally Austrian chancellor in April 1970, Wiesenthal pointed out to the press that four of his new cabinet appointees had been members of the Nazi Party. Kreisky, angry, called Wiesenthal a "Jewish fascist", likened his organisation to the Mafia, and accused him of collaborating with the Nazis. Wiesenthal successfully sued for libel, the suit ending in 1989. In 1986, Wiesenthal was involved in the example of Kurt Waldheim, whose service in the Wehrmacht and likely noesis of the Holocaust were revealed in the lead-up to the 1986 Austrian presidential elections. Wiesenthal, embarrassed that he had previously cleared Waldheim of any wrongdoing, suffered much negative publicity as a result of this event.

With a reputation as a storyteller, Wiesenthal was the author of several memoirs containing tales that are just loosely based on bodily events.[1] [2] In particular, he exaggerated his part in the capture of Eichmann in 1960.[3] [four] Wiesenthal died in his sleep at age 96 in Vienna on 20 September 2005 and was buried in the city of Herzliya in Israel. The Simon Wiesenthal Center, headquartered in Los Angeles, is named in his honour.

Early life [edit]

Simon Wiesenthal (circa 1940–1945)

Wiesenthal was born on 31 December 1908, in Buczacz (Buchach), Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, and so office of Austro-hungarian empire, now Ternopil Oblast, in Ukraine. His begetter, Asher Wiesenthal, was a wholesaler who had emigrated from the Russian Empire in 1905 to escape the frequent pogroms confronting Jews. A reservist in the Austro-Hungarian Regular army, Asher was called to active duty in 1914 at the kickoff of World State of war I. He died in combat on the Eastern Front in 1915. The remainder of the family—Simon, his younger brother Hillel, and his mother Rosa—fled to Vienna as the Russian regular army took control of Galicia. The 2 boys attended a German-linguistic communication Jewish school. The family returned to Buczacz in 1917 afterwards the Russians retreated. The area changed hands several more times before the war ended in November 1918.[5] [6]

Wiesenthal and his brother attended high schoolhouse at the Humanistic Gymnasium in Buchach, where classes were taught in Polish. There Simon met his future wife, Cyla Müller, whom he would marry in 1936. Hillel fell and broke his dorsum in 1923 and died the following year. Rosa remarried in 1926 and moved to Dolyna with her new husband, Isack Halperin, who owned a tile factory there. Wiesenthal remained in Buczacz, living with the Müller family unit, until he graduated from high school—on his second effort—in 1928.[seven] [8] [9]

With an interest in fine art and cartoon, Wiesenthal chose to study compages. His first choice was to attend the Lwów Polytechnic, merely he was turned abroad because the school's Jewish quota had already been filled. He instead enrolled at the Czech Technical University in Prague, where he studied from 1928 until 1932. He was apprenticed every bit a edifice engineer through 1934 and 1935, spending virtually of that menstruation in Odessa. He married Cyla in 1936 when he returned to Galicia.[10] [eleven]

Sources give differing reports of what happened next. Wiesenthal'southward autobiographies contradict each other on many points; he too over-dramatised and mythologised events.[one] [2] One version has Wiesenthal opening an architectural part and finally being admitted to the Lwów Polytechnic for an avant-garde degree. He designed a tuberculosis sanatorium and some residential buildings during the grade of his studies and was agile in a student Zionist arrangement. He wrote for the Passenger vehicle, a satirical student paper, and graduated in 1939.[12] [13] Author Guy Walters states that Wiesenthal's earliest autobiography does not mention studies at Lwów. Walters quotes a curriculum vitae Wiesenthal prepared after World War II as stating he worked as a supervisor at a manufactory until 1939 and then worked as a mechanic in a different factory until the Nazis invaded in 1941. Wiesenthal'due south 1961 book Ich jagte Eichmann (I chased Eichmann)[14] states that he worked in Odessa as an engineer from 1940 to 1941. Walters says that there is no record of Wiesenthal attending the academy at Lwów, and that he does not appear in the Katalog Architektów i Budowniczych (Catalogue of Architects and Builders) for the advisable period.[15]

World State of war 2 [edit]

In Europe, World War II began in September 1939 with the Nazi invasion of Poland. Every bit a effect of the partitioning of Poland under the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact between Frg and the Soviet Marriage, the city of Lwów was annexed by the Soviets and became known as Lvov in Russian or Lviv in Ukrainian. Wiesenthal's stepfather, withal living in Dolyna, was arrested as a capitalist; he later on died in a Soviet prison house. Wiesenthal's mother moved to Lvov to live with Wiesenthal and Cyla. Wiesenthal bribed an official to prevent his own deportation under Clause xi, a rule that prevented all Jewish professionals and intellectuals from living within 100 kilometres (62 mi) of the city, which was nether Soviet occupation until the Germans invaded in June 1941.[16] [17]

By mid-July Wiesenthal and other Jewish residents had to register to do forced labour. Within half dozen months, in November 1941 the Nazis had set up the Lwów Ghetto using Jewish forced labour. All Jews had to give up their homes and motility there, a procedure completed in the following months.[xviii] [19] Several thousand Jews were murdered in Lvov past Ukrainian nationals and German Einsatzgruppen in June and July 1941.[twenty] In his autobiographies, Wiesenthal tells how he was arrested on six July, but saved from execution by his sometime foreman, a man named Bodnar, who was now a member of the Ukrainian Auxiliary Constabulary.[21] At that place are several versions of the story, which may be apocryphal.[22]

In late 1941, Wiesenthal and his wife were transferred to Janowska concentration military camp and forced to piece of work at the Eastern Railway Repair Works. He painted swastikas and other inscriptions on captured Soviet railway engines, and Cyla was put to work polishing the brass and nickel. In exchange for providing details about the railways, Wiesenthal obtained false identity papers for his wife from a fellow member of the Armia Krajowa, a Polish undercover system. She travelled to Warsaw, where she was put to piece of work in a German radio factory. She spent time in two labour camps every bit well. Conditions were harsh and her health was permanently damaged, but she survived the war. The couple was reunited in 1945, and their daughter Paulinka was born the following year.[23] [24] [25]

Every few weeks, the Nazis staged a roundup in the Lvov ghetto of people unable to work. These roundups typically took place while the able-bodied were absent doing forced labour. In one such deportation, Wiesenthal's mother and other elderly Jewish women were transported by freight train to Belzec extermination campsite and murdered in August 1942. Around the aforementioned time, a Ukrainian policeman shot Cyla's mother to death on the front porch of her home in Buczacz while she was being evicted. Between Cyla and Simon Wiesenthal, 89 of their relatives were murdered during the Holocaust.[26]

Forced labourers for the Eastern Railway were eventually kept in a separate closed camp, where conditions were a piddling meliorate than at the main military camp at Janowska. Wiesenthal prepared architectural drawings for Adolf Kohlrautz, the senior inspector, who submitted them under his own name. To obtain contracts, construction companies paid bribes to Kohlrautz, who shared some of the money with Wiesenthal. He was able to laissez passer along farther information nigh the railroads to the secret and occasionally left the compound to obtain supplies, even clandestinely obtaining weapons for the Armia Krajowa and two pistols for himself, which he brought with him when he escaped in late 1943.[27]

According to Wiesenthal, on 20 Apr 1943, Second Lieutenant Gustav Wilhaus, second in command at the Janowska camp, decided to shoot 54 Jewish intellectuals in celebration of Hitler's 54th birthday. Unable to find plenty such people withal alive at Janowska, Wilhaus ordered a roundup of prisoners from the satellite camps. Wiesenthal and 2 other inmates were taken from the Eastern Railway camp to the execution site, a trench 6 feet (i.8 m) deep and 1,500 feet (460 thou) long at a nearby sandpit. The men were stripped and led through "the Hose", a six- or 7-foot wide barbed wire corridor to the execution ground. The victims were shot and their bodies immune to autumn into the pit. Wiesenthal, waiting to be shot, heard someone call out his proper name. He was returned alive to the camp; Kohlrautz had convinced his superiors that Wiesenthal was the best man available to paint a giant poster in honour of Hitler'southward birthday.[28] [29]

On two Oct 1943, according to Wiesenthal, Kohlrautz warned him that the military camp and its prisoners were nearly to be liquidated. Kohlrautz gave Wiesenthal and fellow prisoner Arthur Scheiman passes to become to town, accompanied by a Ukrainian baby-sit, to buy stationery. The two men escaped out the dorsum of the shop while their guard waited at the front counter.[30] [31]

Wiesenthal did non mention either of these events—or Kohlrautz'south part in them—when testifying to American investigators in May 1945, or in an affidavit he made in August 1954 about his wartime persecutions, and researcher Guy Walters questions their actuality. Wiesenthal variously reported that Kohlrautz was killed on the Soviet Front in 1944 or in the Boxing of Berlin on 19 Apr 1945.[30]

Prisoners at Mauthausen greet American forces, May 1945

After several days in hiding, Scheiman rejoined his married woman, and Wiesenthal was taken by members of the surreptitious to the nearby village of Kulparkow, where he remained until the end of 1943. Soon afterwards the Janowska campsite was liquidated; this fabricated it unsafe to hibernate in the nearby countryside, so Wiesenthal returned to Lvov, where he spent iii days hiding in a cupboard at the Scheimans' apartment. He then moved to the apartment of Paulina Busch, for whom he had previously forged an identity carte du jour. He was arrested there, hiding under the floorboards, on thirteen June 1944 and taken back to the remains of the camp at Janowska. Wiesenthal tried but failed to commit suicide to avert existence interrogated about his connections with the underground. In the stop in that location was no time for interrogations, as Soviet forces were advancing into the area. SS-Hauptsturmführer Friedrich Warzok, the new military camp commandant, rounded up the remaining prisoners and transported them to Przemyśl, 97 kilometres (lx mi) due west of Lvov, where he put them to work building fortifications. By September Warzok and his men were reassigned to the front, and Wiesenthal and the other surviving captives were sent to the Kraków-Płaszów concentration military camp.[32] [33]

By October the inmates were evacuated to Gross-Rosen concentration camp, where inmates were suffering from severe overcrowding and a shortage of food. Wiesenthal's big toe on his right foot had to exist amputated afterward a rock fell on it while he was working in the quarry. He was notwithstanding ill in January when the advancing Soviets forced nonetheless another evacuation, this fourth dimension on foot, to Chemnitz. Using a broom handle for a walking stick, he was one of the few who survived the march. From Chemnitz the prisoners were taken in open freight cars to Buchenwald, and a few days later past truck to Mauthausen concentration camp, arriving in mid-Feb 1945. Over one-half the prisoners did not survive the journeying. Wiesenthal was placed in a death cake for the mortally ill, where he survived on 200 calories a day until the army camp was liberated by the Americans on 5 May 1945. He weighed 41 kilograms (90 lb) when he was liberated.[34] [35]

Nazi hunter [edit]

Within three weeks of the liberation of Mauthausen, Wiesenthal had prepared a listing of effectually a hundred names of suspected Nazi war criminals—more often than not guards, camp commandants, and members of the Gestapo—and presented information technology to a War Crimes part of the American Counterintelligence Corps at Mauthausen. He worked as an interpreter, accompanying officers who were carrying out arrests, though he was nevertheless very delicate. When Austria was partitioned in July 1945, Mauthausen vicious into the Soviet-occupied zone, so the American War Crimes Part was moved to Linz. Wiesenthal went with them, and was housed in a displaced persons campsite. He served as vice-chairman of the area'southward Jewish Central Committee, an organisation that attempted to arrange basic care for Jewish refugees and tried to help people gather information about their missing family unit members.[36] [37]

Wiesenthal worked for the American Role of Strategic Services for a twelvemonth, and continued to collect data on both victims and perpetrators of the Holocaust. He assisted the Berihah, an underground organization that smuggled Jewish survivors into the British Mandate for Palestine. Wiesenthal helped conform for forged papers, nutrient supplies, transportation, and so on. In February 1947, he and xxx other volunteers founded the Jewish Documentation Center in Linz to gather information for future war crimes trials.[38] [39] They collected 3,289 depositions from concentration camp survivors notwithstanding living in Europe.[40] Even so, equally the U.s.a. and the Soviet Union lost interest in conducting further trials, a similar group headed past Tuviah Friedman in Vienna airtight its office in 1952, and Wiesenthal's closed in 1954. Almost all of the documentation nerveless at both centres was forwarded to the Yad Vashem archives in Israel.[41] Wiesenthal, employed total-time by two Jewish welfare agencies, continued his work with refugees.[42] Every bit it became clear that the former Allies were no longer interested in pursuing the piece of work of bringing Nazi state of war criminals to justice, Wiesenthal persisted, assertive the survivors were obliged to take on the job.[xl] His piece of work became a style to memorialise and call back all the people that had been lost.[43] He told biographer Alan Levy in 1974:

When the Germans get-go came to my city in Galicia, one-half the population was Jewish: one hundred 50 thousand Jews. When the Germans were gone, 5 hundred were alive. ... Many times I was thinking that everything in life has a price, so to stay live must also have a cost. And my toll was always that, if I lived, I must be deputy for many people who are not live.[43]

Adolf Eichmann [edit]

Though almost of the Jews all the same alive in Linz had emigrated later on the war, Wiesenthal decided to stay on, partly because the family of Adolf Eichmann lived a few blocks away from him.[44] [45] Eichmann had been in charge of the transportation and deportation of Jews in the Nazi Terminal Solution to the Jewish Question: a plan, finalised at the Wannsee Conference—at which Eichmann took the minutes—to exterminate all the Jews in Europe.[46] After the war, Eichmann hid in Austria using forged identity papers until 1950, when he left via Italian republic and moved to Argentine republic under an assumed proper name.[47] [48] Hoping to obtain data on Eichmann's whereabouts, Wiesenthal continuously monitored the remaining members of the immediate family in Linz until they vanished in 1952.[49]

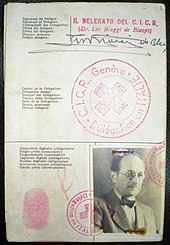

Document under the name of Ricardo Klement that Adolf Eichmann used to enter Argentina in 1950

Wiesenthal learned from a letter shown to him in 1953 that Eichmann had been seen in Buenos Aires, and he passed forth that information to the Israeli consulate in Vienna in 1954.[50] Fritz Bauer, prosecutor-general of the state of Hesse in West Germany, received independent confirmation of Eichmann'due south whereabouts in 1957, but German agents were unable to detect him until belatedly 1959.[51] When Eichmann'south father died in 1960, Wiesenthal fabricated arrangements for private detectives to surreptitiously photo members of the family, as Eichmann's brother Otto was said to bear a strong family resemblance and there were no current photos of the fugitive. He provided these photographs to Mossad agents on 18 February.[52] Zvi Aharoni, one of the Mossad agents responsible for Eichmann's capture in Buenos Aires on 11 May 1960, said the photos were useful in confirming Eichmann'southward identity.[53] On 23 May Israeli Prime number Minister David Ben-Gurion announced Eichmann was nether arrest and in Israel. The next day Wiesenthal, while he was being interviewed by reporters, received a congratulatory telegram from Yad Vashem. He immediately became a modest glory, and began work on a volume about his experiences. Ich jagte Eichmann: Tatsachenbericht (I chased Eichmann. A true story)[14] was published half-dozen weeks before the trial opened in spring 1961. Wiesenthal helped the prosecution set their case and attended a portion of the trial.[54] Eichmann was sentenced to death and was hanged on one June 1962.[47]

Meanwhile, both of Wiesenthal's employers terminated his services in 1960, as there were too few refugees left in the city to justify the expense.[55] Wiesenthal opened a new documentation centre (the Documentation Middle of the Association of Jewish Victims of the Nazi Government) in Vienna in 1961. He became a Mossad operative, for which he received the equivalent of several hundred dollars per month.[56] He maintained files on hundreds of suspected Nazi war criminals and located many, about 6 of whom were arrested every bit a result of his activities. Successes included locating and bringing to trial Erich Rajakowitsch, responsible for the deportation of Jews from the Netherlands,[57] and Franz Murer, the commandant of the Vilna Ghetto.[58] In 1963 Wiesenthal read in the newspaper that Karl Silberbauer, the human who had arrested famed diarist Anne Frank, had been located; he was serving on the constabulary force in Vienna. Wiesenthal'south publicity campaign led to Silberbauer existence temporarily suspended from the force, but he was never prosecuted for absorbing the Frank family.[59]

Despite Wiesenthal's protests, in late 1963 his centre in Vienna was taken over by a local community group, so he immediately set upward a new independent office, funded using donations and his stipend from the Mossad.[lx] Equally the twenty-year statute of limitations for German war crimes was well-nigh to expire, Wiesenthal began lobbying to have it extended or removed entirely. In March 1965 the Bundestag deferred the matter for five years, effectively extending the expiration appointment. Similar action was taken by the Austrian government.[59] Simply as time went on, it became more difficult to obtain prosecutions. Witnesses grew older and were less likely to be able to offer valuable testimony. Funding for trials was inadequate, equally the governments of Austria and Germany became less interested in obtaining convictions for wartime events, preferring to forget the Nazi past.[61]

Franz Stangl [edit]

Franz Stangl was a supervisor at the Hartheim Euthanasia Centre, part of Action T4, an early Nazi euthanasia programme that was responsible for the deaths of over 70,000 mentally ill or physically deformed people in Germany. In February 1942, he was commander at the Sobibor extermination camp and in August of the same yr he was transferred to Treblinka. During his time at these camps, he oversaw the deaths of nigh 900,000 people.[62] [63] While under U.Due south. detention for two years, he remained unidentified as a war criminal because then few witnesses had survived Sobibor and Treblinka that authorities never realised who he was. He escaped while on a roadwork item in Linz in May 1948.[64] After he made his fashion to Rome, the Caritas relief agency provided him with a Cherry Cross passport and a gunkhole ticket to Syria.[65] His family unit joined him there a year later and they emigrated to Brazil in 1951.[66]

It was probably Stangl's former son-in-law who informed Wiesenthal of Stangl's whereabouts in 1964.[67] Concerned that Stangl would be warned and escape, Wiesenthal quietly prepared a dossier with the assistance of Austrian Minister of Justice Hans Klecatsky.[68] Stangl was arrested exterior his home in São Paulo on 28 Feb 1967 and was extradited to Deutschland on 22 June.[69] A month after Wiesenthal's volume The Murderers Amid United states was released. Wiesenthal's publishers advertised that he had been responsible for locating over 800 Nazis, a claim that had no basis in fact but was yet repeated by reputable newspapers such as the New York Times.[70] Stangl was sentenced to life in prison and died of eye failure in June 1971, having confessed his guilt to biographer Gitta Sereny the previous solar day.[71]

Hermine Braunsteiner [edit]

Known as "the Mare of Majdanek", Hermine Braunsteiner was a guard who served at Majdanek and Ravensbrück concentration camps. A cruel and sadistic woman, she earned her nickname for her propensity to kicking her victims to decease.[72] She served a three-year sentence in Republic of austria for her activities in Ravensbrück, but had not still been charged for any of her crimes at Majdanek when she emigrated to the United States in 1959. She became an American citizen in 1963.[73]

Wiesenthal was offset told about Braunsteiner in early 1964 via a adventure encounter in Tel Aviv with someone who had seen her performing selections at Majdanek—deciding who was to be assigned to slave labour and who was to murdered immediately in the gas chambers. When he returned to Vienna he had an operative visit one of her relatives to clandestinely collect data. Wiesenthal soon traced Braunsteiner's whereabouts to Queens, New York, so he notified the Israeli constabulary and the New York Times.[74] Despite Wiesenthal's efforts to expedite the affair, Braunsteiner was not extradited to Germany until 1973. Her trial was part of a joint indictment with ix other defendants accused of killing 250,000 people at Majdanek. She was sentenced to life imprisonment in 1981 and died in 1999.[75] [76]

Josef Mengele [edit]

Josef Mengele was a medical officer assigned to Auschwitz concentration camp from 1943 until the finish of the state of war. Too as making near of the selections of inmates as they arrived by train from all over Europe, he performed unscientific and normally mortiferous experiments on the inmates.[77] He left the campsite in January 1945 as the Cherry-red Regular army approached and was briefly in American custody in Weiden in der Oberpfalz, but was released.[78] He took piece of work every bit a farm paw in rural Deutschland, remaining until 1949, when he decided to flee the land. He acquired a Red Cross passport and left for Argentina,[79] setting up a business in Buenos Aires in 1951.[fourscore] Acting on information received from Wiesenthal, West High german authorities tried to extradite Mengele in 1960, but he could not be found; he had in fact moved to Paraguay in 1958.[81] [82] He moved to Brazil in 1961 and lived there until his death in 1979.[83]

Wiesenthal claimed to accept information that placed Mengele in several locations: on the Greek island of Kythnos in 1960,[84] Cairo in 1961,[85] in Spain in 1971,[86] and in Paraguay in 1978, the latter eighteen years subsequently he had left.[87] In 1982, he offered a reward of $100,000 for Mengele's capture and insisted as belatedly every bit 1985—six years subsequently Mengele'southward death—that he was nevertheless alive.[88] The Mengele family admitted to government in 1985 that he had died in 1979; the body was exhumed and its identity was confirmed.[89] Earlier that twelvemonth Wiesenthal had served as one of the judges at a mock trial of Mengele, held in Jerusalem.[ninety]

Simon Wiesenthal Heart [edit]

The Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles was founded in 1977 by Rabbi Marvin Hier, who paid Wiesenthal an honorarium for the right to utilise his proper noun.[91] The center helped with the campaign to remove the statute of limitations on Nazi crimes and continues the hunt for suspected Nazi war criminals, merely today its primary activities include Holocaust remembrance, pedagogy, and fighting antisemitism.[92] [93] Wiesenthal was not always happy with the way the middle was run. He thought the centre's Holocaust museum was not dignified plenty and that he should accept a larger say in the overall operations. He even wrote to the Board of Directors requesting Hier'due south removal, but in the end had to be content with beingness a figurehead.[94]

Afterwards life [edit]

Austrian politics [edit]

Bruno Kreisky [edit]

Before long later Bruno Kreisky was inaugurated as Austrian chancellor in Apr 1970, Wiesenthal pointed out to the printing that iv of his new cabinet appointees had been members of the Nazi Party. In an address in June, Kreisky'southward Minister of Instruction and Culture Leopold Gratz characterised Wiesenthal's Documentation Eye of the Association of Jewish Victims of the Nazi Authorities as a private spy ring, invading the privacy of innocent parties. In an interview a week later, Kreisky himself described Wiesenthal as a "Jewish fascist", a remark he later denied making. Wiesenthal discovered that he would be unable to sue, because under Austrian law Kreisky was protected past parliamentary immunity.[95] [96]

When his re-election in 1975 seemed unsure, Kreisky proposed that his Social Democratic Political party should class a coalition with the Freedom Political party, headed by Friedrich Peter. Wiesenthal had documents proving that Peter had been a fellow member of the 1 SS Infantry Brigade, a unit that had exterminated over 13,000 Jewish civilians in Ukraine in 1941–42. He decided non to reveal this information to the press until after the election, only forwarded his dossier to President Rudolf Kirchschläger. Peter denied having participated in, or having cognition of, any atrocities. In the end, Kreisky's party won a clear bulk and did non class the coalition.[97]

In a press briefing a curt time later on the election and Wiesenthal'due south revelations, Kreisky said Wiesenthal used "the methods of a quasi-political Mafia."[98] Wiesenthal filed a libel lawsuit (although Kreisky had the power to declare immunity if he then chose), and when Kreisky after defendant Wiesenthal of beingness an amanuensis of the Gestapo, working with the Judenrat in Lvov, these accusations were incorporated into the lawsuit besides.[99] The arrange was decided in Wiesenthal'southward favour in 1989, but after Kreisky's death nine months later his heirs refused to pay. When the relevant archives were later opened for research, no evidence was constitute that Wiesenthal had been a collaborator.[100]

Kurt Waldheim [edit]

When Kurt Waldheim was named secretary-general of the United Nations in 1971, Wiesenthal reported—without checking very thoroughly—that at that place was no testify that he had a Nazi past.[101] This analysis had been supported by the opinions of the American Counterintelligence Corps and Office of Strategic Services when they examined his records right after the war.[102] However, Waldheim's 1985 autobiography did not include his state of war service post-obit his recuperation from a 1941 injury. When he returned to active duty in 1942, he was posted to Yugoslavia and Hellenic republic, and had cognition of murders of civilians that took place in those locations during his service in that location.[103] The Austrian news magazine Profil published a story in March 1986—during his campaign for the presidency of Austria—that Waldheim had been a member of the Sturmabteilung (SA). The New York Times shortly reported that Waldheim had failed to reveal all of the facts about his war service. Wiesenthal, embarrassed, attempted to help Waldheim defend himself.[104] The World Jewish Congress investigated the issue, but the Israeli attorney full general ended that their material was insufficient bear witness for a conviction. Waldheim was elected president in July 1986.[105] A console of historians tasked with investigating the case issued a study eighteen months later. They ended that, while there was no evidence that Waldheim had committed atrocities, he must accept known they were occurring, yet did nothing. Wiesenthal unsuccessfully demanded that Waldheim resign. The World Jewish Congress successfully lobbied to have Waldheim barred from entering the United States.[106]

Sails of Hope [edit]

In 1968, Wiesenthal published Zeilen der hoop. De geheime missie van Christoffel Columbus (translated in 1972 as Sails of Hope: The Hush-hush Mission of Christopher Columbus), which was his offset non-fiction book not on the bailiwick of the Holocaust. In the volume, Wiesenthal put forwards his theory that Christopher Columbus was a Sephardi Jew from Espana who practised his religion in secret to avoid persecution. (The consensus of near historians is that Columbus came from the Republic of Genoa, on the northwestern declension of present-mean solar day Italian republic). Wiesenthal argued that the quest for the New Earth was non motivated by wealth or fame, but rather past Columbus'due south desire to find a place of refuge for the Jews, who were suffering immense persecution in Espana at the time (and in 1492 would be subjected to the Edict of Expulsion). Wiesenthal as well believed that Columbus's concept of "sailing west" was based on Biblical prophecies (certain verses in the Book of Isaiah) rather than any prior geographical noesis.[107]

Awards and nominations [edit]

Wiesenthal was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1985, the fortieth ceremony of the terminate of the war. Rumour had it that the Nobel Committee would give the prize to a Holocaust-related candidate. Fellow Holocaust survivor and writer Elie Wiesel, too nominated, began a entrada in hopes of winning the prize, travelling to France, Ethiopia and Oslo for speaking tours and humanitarian work. Rabbi Hier of the Wiesenthal Centre urged Wiesenthal to antechamber for the prize as well, simply other than delivering a lecture in Oslo, Wiesenthal did trivial to promote his candidacy. When Wiesel was awarded the 1986 prize, Wiesenthal claimed the World Jewish Congress must have influenced the commission's decision, a claim the WJC denied. Biographer Tom Segev speculates that the loss may take been because of the negative publicity over the Waldheim affair.[108]

In 1992, Wiesenthal was awarded the Erasmus Prize by the Praemium Erasmianum Foundation.[109]

In 2004, he was awarded an honorary KBE by the British Government.[110]

Retirement and death [edit]

Wiesenthal received many death threats over the years. After a bomb placed past neo-Nazis exploded outside his house in Vienna on 11 June 1982, law guards were stationed outside his home 24 hours a day.[111] Cyla plant the stressful nature of her husband's career and the dragged-out legal matters regarding Kreisky to be overwhelming, and she sometimes suffered from depression.[111]

Wiesenthal spent time at his office at the Documentation Centre of the Association of Jewish Victims of the Nazi Authorities in Vienna even as he approached his 90th altogether.[112] He finally retired in October 2001, when he was 92.[113] The terminal Nazi he had a hand in bringing to trial was Untersturmführer Julius Viel, who was convicted in 2001 of shooting seven Jewish prisoners.[112] [114] "I accept survived them all. If there were any left, they'd be too onetime and weak to stand trial today. My piece of work is washed," said Wiesenthal.[115] Cyla died on 10 November 2003, at age 95, and Wiesenthal died on xx September 2005, age 96. He was buried in Herzliya, Israel.[116]

In a statement on Wiesenthal's death, Council of Europe chairman Terry Davis said, "Without Simon Wiesenthal's relentless effort to find Nazi criminals and bring them to justice, and to fight anti-Semitism and prejudice, Europe would never have succeeded in healing its wounds and reconciling itself. He was a soldier of justice, which is indispensable to our freedom, stability and peace."[117]

In 2010 the Austrian and Israeli governments jointly issued a commemorative postage honouring Wiesenthal. Wiesenthal became an avid stamp collector subsequently the war, following advice from his doctors to have up a hobby to assistance him relax.[42] In 2006 his drove of Zemstvo stamps sold at auction for €ninety,000 after his death.[119]

Dramatic portrayals [edit]

Wiesenthal was portrayed past Israeli actor Shmuel Rodensky in the flick adaptation of Frederick Forsyth's The Odessa File (1974). Afterwards the movie's release, Wiesenthal received many reports of sightings of the subject of the film, Eduard Roschmann, commandant of the Riga Ghetto. These sightings proved to be false alarms, but in 1977 a person living in Buenos Aires who saw the movie reported to police force that Roschmann was living nearby. The fugitive escaped to Paraguay, where he died of a center attack a month later.[120] In Ira Levin's novel The Boys from Brazil, the grapheme of Yakov Liebermann (called Ezra Liebermann and played past Laurence Olivier in the film) is modelled on Wiesenthal. Olivier visited Wiesenthal, who offered communication on how to play the part. Wiesenthal attended the film's New York premiere in 1978.[121] Ben Kingsley portrayed him in the HBO moving picture Murderers Among U.s.: The Simon Wiesenthal Story (1989).[122] Judd Hirsch portrayed him in the Amazon Prime Video series Hunters (2020).[123]

Wiesenthal has been the subject of several documentaries. The Art of Remembrance: Simon Wiesenthal was produced in 1994 by filmmakers Hannah Heer and Werner Schmiedel for River Lights Pictures.[124] The documentary I Have Never Forgotten Y'all: The Life and Legacy of Simon Wiesenthal, narrated past Nicole Kidman, was released by Moriah Films in 2007.[125] Wiesenthal is a 1-person evidence written and performed past Tom Dugan that premiered in 2014.[126]

Autobiographical inconsistencies [edit]

A number of Wiesenthal'southward books contain conflicting stories and tales, many of which were invented.[1] [2] Several authors, including Segev[1] and British author Guy Walters,[2] feel that Wiesenthal'southward autobiographies are not reliable sources of information nearly his life and activities. For example, Wiesenthal would describe 2 people fighting over ane of the lists he had prepared of survivors of the Holocaust; the two wait up and recognise each other and have a bawling reunion. In ane account information technology is a husband and married woman,[127] and in another telling it is two brothers.[128] Wiesenthal's memoirs variously claim he had spent time in as many every bit eleven concentration camps; the actual number was 5.[129] A drawing he made in 1945 that he claimed was a scene he witnessed in Mauthausen had actually been sketched from photos that appeared in Life magazine that June.[130] [131] He peculiarly over-emphasised his office in the capture of Eichmann, claiming that he prevented Veronika Eichmann from having her husband declared dead in 1947, when in fact the declaration was denied by government officials.[132] Wiesenthal said that he had retained his Eichmann file when he sent his research materials to Yad Vashem in 1952; in fact he sent all his materials at that place,[133] and it was his analogue, Tuviah Friedman in Vienna, who had retained materials on Eichmann.[134] Isser Harel, manager of the Mossad at the time, has stated that Wiesenthal had no role in the capture of Eichmann.[3] [4]

Walters and Segev both noted inconsistencies between Wiesenthal's stories and his bodily achievements. Segev concluded that Wiesenthal lied because of his storytelling nature and survivor guilt.[135] Daniel Finkelstein described Walters'southward inquiry in Hunting Evil every bit impeccable and quoted Ben Barkow: "Accepting that Wiesenthal was a showman and a braggart and, yes, even a liar, tin live alongside acknowledging the contribution he made".[136]

In 1979, Wiesenthal told The Washington Post: "I take sought with Jewish leaders non to talk almost 6 million Jewish dead [in the Holocaust], but rather nearly 11 million civilians expressionless, including 6 million Jews." In a 2017 interview, Yehuda Bauer said that he had told Wiesenthal not to utilize this effigy. "I said to him, 'Simon, you lot are telling a lie,' ... [Wiesenthal replied] 'Sometimes you need to practise that to become the results for things you retrieve are essential.'" Co-ordinate to Bauer and other historians, Wiesenthal chose the effigy of v million non-Jewish victims because it was just lower than the half-dozen million Jews who were murdered, but high enough to attract sympathy from non-Jews. The figure of xi million Nazi victims became popular and was referred to by President Jimmy Carter in the executive order establishing the U.s.a. Holocaust Memorial Museum.[137]

Listing of books and journal manufactures [edit]

Books [edit]

- Ich jagte Eichmann. Tatsachenbericht (I chased Eichmann. A true story). S. Mohn, Gütersloh (1961)

- Writing nether the pen name Mischka Kukin, Wiesenthal published Humor hinter dem Eisernen Vorhang ("Sense of humor Behind the Iron Curtain"). Gütersloh: Signum-Verlag (1962)

- The Murderers Amid The states: The Simon Wiesenthal Memoirs. New York: McGraw-Colina (1967)

- Zeilen der hoop. De geheime missie van Christoffel Columbus. Amsterdam: H. J. W. Becht (1968). Translated as Sails of Hope: The Cloak-and-dagger Mission of Christopher Columbus. New York: Macmillan (1972)

- "Mauthausen: Steps beyond the Grave". In Hunter and Hunted: Human History of the Holocaust. Gerd Korman, editor. New York: Viking Printing (1973). pp. 286–295.

- The Sunflower: On the Possibilities and Limits of Forgiveness New York: Schocken Books (1969)

- Max and Helen: A Remarkable True Dearest Story. New York: Morrow (1982)

- Every Day Remembrance Day: A Chronicle of Jewish Martyrdom. New York: Henry Holt (1987)

- Justice, Not Vengeance. New York: Grove-Weidenfeld (1989)

Journal articles [edit]

- "Latvian War Criminals in USA". Jewish Currents 20, no. vii (July/Baronial 1966): four–eight. Besides in xx, no. 10 (November 1966): 24.

- "There Are Still Murderers Among United states of america". National Jewish Monthly 82, no. 2 (October 1967): eight–9.

- "Nazi Criminals in Arab States". In Israel Horizons 15, no. vii (September 1967): x–12.

- Anti-Jewish Agitation in Poland: (Prewar Fascists and Nazi Collaborators in Unity of Action with Antisemites from the Ranks of the Smooth Communist Political party): A Documentary Written report. Bonn: R. Vogel (1969)

- "Justice: Why I Hunt Nazis". In Jewish Observer and Middle East Review 21, no. 12 (24 March 1972): xvi.

Meet also [edit]

- Vienna Wiesenthal Institute for Holocaust Studies

- List of awards received by Simon Wiesenthal

- Beate Klarsfeld

- Serge Klarsfeld

- Yaron Svoray

- Efraim Zuroff

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d Segev 2010, p. 27.

- ^ a b c d Walters 2009, pp. 77–78.

- ^ a b Segev 2010, p. 278.

- ^ a b Levy 2006, pp. 158–160.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. fifteen, 17–19.

- ^ Segev 2010, p. 35.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 36–38.

- ^ Walters 2009, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Levy 2006, p. 20.

- ^ Walters 2009, p. 83.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 25, 27.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 21, 25–26.

- ^ a b Wiesenthal 1961.

- ^ Walters 2009, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 31.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 41–43.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 31–35.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 44–47.

- ^ Evans 2008, p. 223.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 32–34.

- ^ Walters 2009, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Levy 2006, p. 37.

- ^ Walters 2009, p. 87.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 50, 73.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Segev 2010, p. 50.

- ^ Walters 2009, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 46, 48–49.

- ^ a b Walters 2009, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 52–58, 63.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 54–61.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 63–69.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 61–63.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 75–77.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 76–77.

- ^ a b Walters 2009, p. 98.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 139, 143.

- ^ a b Segev 2010, p. 122.

- ^ a b Levy 2006, p. 5.

- ^ Levy 2006, p. 146.

- ^ Segev 2010, p. 127.

- ^ Evans 2008, pp. 266–267.

- ^ a b Evans 2008, p. 747.

- ^ Levy 2006, p. 136.

- ^ Levy 2006, p. 138.

- ^ Walters 2009, p. 286.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 135–141.

- ^ Walters 2009, p. 281.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 148–152.

- ^ Segev 2010, p. 146.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 157, 166, 182.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 172–173.

- ^ a b Segev 2010, pp. 173–176.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 180–181, 185.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 226, 250, 376.

- ^ Walters 2009, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 328, 336.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 359–360.

- ^ Levy 2006, p. 363.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 368–369.

- ^ Walters 2009, p. 334.

- ^ Levy 2006, p. 374.

- ^ Walters 2009, p. 225.

- ^ Walters 2009, pp. 336–337.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 378–379.

- ^ Walters 2009, p. 357.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 387–388.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 358–359.

- ^ Levy 2006, p. 403.

- ^ Levy 2006, p. 241.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 255, 257.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 258, 263.

- ^ Levy 2006, p. 266.

- ^ Walters 2009, p. 316.

- ^ Levy 2006, p. 269.

- ^ Levy 2006, p. 295.

- ^ Segev 2010, p. 167.

- ^ Walters 2009, p. 317.

- ^ Walters 2009, p. 370.

- ^ Levy 2006, p. 296.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 297, 301.

- ^ Segev 2010, p. 339.

- ^ Levy 2006, p. 251.

- ^ Walters 2009, p. 398.

- ^ Walters 2009, p. 407.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 352, 354.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 360–361.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 410–413.

- ^ Segev 2010, p. 245.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 417–419.

- ^ Segev 2010, p. 282.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 283–284.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 309–310.

- ^ Segev 2010, p. 365.

- ^ Levy 2006, p. 466.

- ^ Levy 2006, pp. 428, 432, 435, 448.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 370–371.

- ^ Segev 2010, p. 373.

- ^ Segev 2010, p. 374.

- ^ Wiesenthal & de Metz 1968.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 376–378.

- ^ Praemium Erasmianum Foundation.

- ^ Pick 2004.

- ^ a b Segev 2010, p. 305.

- ^ a b Segev 2010, pp. 406–407.

- ^ Leidig 2001.

- ^ Los Angeles Times, 27 Feb 2002.

- ^ Haaretz obituary, 20 September 2005.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 406, 408.

- ^ Haaretz, 20 September 2005.

- ^ Kandell 2010.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 260–261, 263.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 332–333.

- ^ Simon Wiesenthal Archive.

- ^ Hawson 2020.

- ^ Brennan 2013.

- ^ The Village Voice review.

- ^ Wong 2014.

- ^ Segev 2010, p. 71.

- ^ Levy 2006, p. 79.

- ^ Segev 2010, pp. 395–396.

- ^ Segev 2010, p. 400.

- ^ Walters 2009, illustrations betwixt pages 278–279.

- ^ Walters 2009, p. 280.

- ^ Walters 2009, pp. 280–281.

- ^ Levy 2006, p. 139.

- ^ Garner 2010.

- ^ Finkelstein 2009.

- ^ Kampeas 2017.

Bibliography [edit]

- Brennan, Sandra (30 Jan 2013). "The Art of Remembrance – Simon Wiesenthal (1994)". Movies & Television Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 January 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- Evans, Richard J. (2008). The 3rd Reich at War. New York: Penguin Group. ISBN978-0-xiv-311671-iv.

- Finkelstein, David (20 August 2009). "It is correct to expose Wiesenthal". The Jewish Chronicle . Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- Garner, Dwight (2 September 2010). "Simon Wiesenthal, the Homo Who Refused to Forget". New York Times . Retrieved ii June 2015.

- Hawson, Fred (29 Baronial 2020). "Amazon Prime review: Al Pacino leads 'Hunters' against Nazis in polarizing serial". ABS-CBN News . Retrieved half dozen December 2020.

- Kampeas, Ron (31 January 2017). "'Remember the 11 million'? Why an inflated victims tally irks Holocaust historians". Jewish Telegraphic Agency . Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- Kandell, Jonathan (xi Feb 2010). "Postage Pays For Norwegian Philatelist". Institutional Investor . Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- Leidig, Michael (vii October 2001). "The chase is over, says Wiesenthal every bit he retires". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Levy, Alan (2006) [1993]. Nazi Hunter: The Wiesenthal File (Revised 2002 ed.). London: Constable & Robinson. ISBN978-1-84119-607-7.

- Pick, Hella (nineteen Feb 2004). "Knighthood for Nazi hunter". The Guardian . Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- Segev, Tom (2010). Simon Wiesenthal: The Life and Legends . New York: Doubleday. ISBN978-0-385-51946-5.

- Staff. "Erasmus Prize: Former Laureates". Praemium Erasmianum Foundation. Archived from the original on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- Staff (27 February 2002). "Julius Viel, 84; Former Nazi Officer Bedevilled of Murdering Jews". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved ten Oct 2019.

- Staff. "Simon Wiesenthal Archive: Filmography". Documentation Middle of the Association of Jewish Victims of the Nazi Government. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- Staff (twenty September 2005). "Simon Wiesenthal, 'censor of the Holocaust,' dies at 96". Haaretz. Amos Schocken. Retrieved 10 Oct 2019.

- Staff (20 September 2005). "Simon Wiesenthal to be laid to remainder Fri in Herzliya". Haaretz. Amos Schocken. Retrieved x October 2019.

- Wallace, Julia (15 May 2007). "I Accept Never Forgotten You lot: The Life and Legacy of Simon Wiesenthal". The Hamlet Vocalisation. Michael Cohen. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- Walters, Guy (2009). Hunting Evil: The Nazi War Criminals Who Escaped and the Quest to Bring Them to Justice. New York: Broadway Books. ISBN978-0-7679-2873-i.

- Wiesenthal, Simon (1961). Ich jagte Eichmann. Tatsachenbericht [I chased Eichmann. A true story]. Gütersloh: S. Mohn.

- Wiesenthal, Simon; de Metz, Max (1968). Zeilen der hoop. De geheime missie van Christoffel Columbus [Sails of Hope: The Clandestine Mission of Christopher Columbus] (in Dutch). Amsterdam: H. J. W. Becht. OCLC 492941413.

- Wong, Curtis (30 October 2014). "Tom Dugan Examines The Heroic (And Comedic) Side Of Simon Wiesenthal In 1-Man Prove". Huffington Postal service . Retrieved 10 Oct 2019.

External links [edit]

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Simon_Wiesenthal

Publicar un comentario for "Simon Wiesenthal It Can Happen Again"